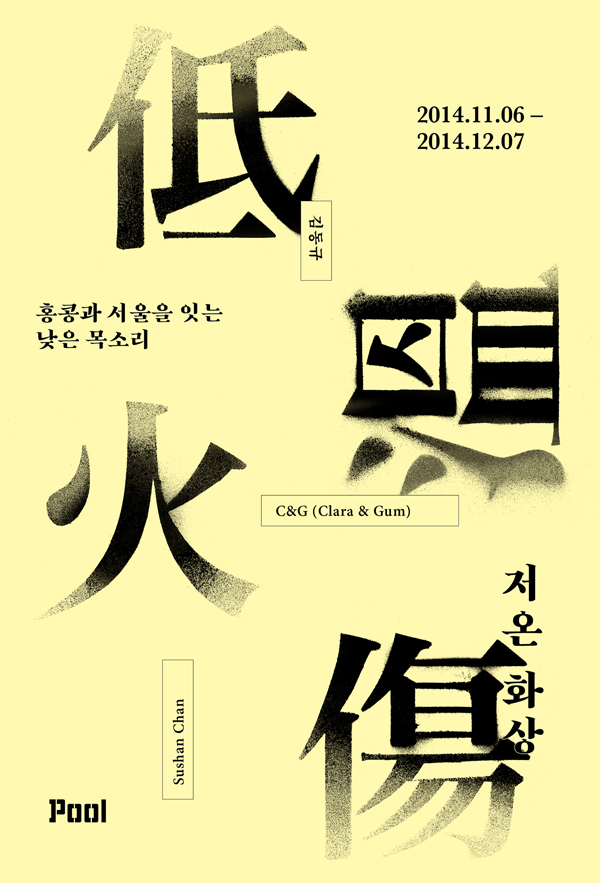

Title: Low Burn: Low Voice connecting Hong Kong and Seoul

Participating artists: Dongkyu Kim, C&G (Clara and Gum), Sushan Chan

Exhibition period: November 6, 2014 - December 7, 2014

Opening Reception: Thursday, November 6, 2014, 7pm.

Artist Talk: Thursday, November 6, 2014, 6pm.

*This event is held with Efes Turkey Beer

Venue: Art Space Pool, Seoul, Korea

Exhibition hour: 10:00 ~ 18:00 (closed on Mondays)

Familiarity, at times, gives rise to acclimation—and the suppression that follows as its consequence. Beginning at some point, a pressure softly approaches that threatens our freedom, but it is imprinted onto us like a kind of a custom; as a result, we are unable to perceive its effect. But as time goes by, one suddenly comes to a realization: it is hot and painful. A “low burn” is caused by familiar objects that we commonly encounter, and although it is brought about by a low temperature, one can suffer burns given continuous exposure. While it may not feel hot initially, the temperature on one’s skin gradually rises to the level of a burn. Nevertheless, for a low burn—which is potentially more lethal than a high burn—a total “skin graft” is sometimes necessary due to the impossibility of self-treatment. That is to say, if one takes no action and does not resist in the face of a certain critical problem, ultimately, this can lead to a result that cannot be undone.

This exhibition examines the works of Dongkyu Kim, C&G (Clara Cheung and Gum Cheng), and Sushan Chan—four artists from Korea and Hong Kong whose works discuss, from the artists’ individually distinct approaches, the actions that they must take before an irreversible pain sets in—and further embodies the journey of the artists’ meeting and mutual exchange. Although Hong Kong and Korea are burdened with distinctly different colonial histories and social conditions, we can locate a connection between Hong Kong and Korea where the current situation in Hong Kong recalls the history of the struggle for democracy in Korea and people in Hong Kong today make reference to Korea’s history of protest. It is evident that the artists participating in this exhibition are confronting different situations, issues, and objectives, and that their individual methods of responding to these circumstances vary. Nevertheless, grasping onto art as their common medium, they break through to articulate their views at an even temperature. This exhibition encapsulates a process whereby the four artists came together in one place, struggled to communicate using different languages, shared and explained their concerns with one another, and attempted to empathize with their counterparts’ problems and concerns.

It could be said that during the British colonial period, Hong Kong was largely free from the weight of ideology and maintained relative economic stability. In 1997, when Hong Kong was returned to China, Hong Kong became a Special Administrative Region of China with some guarantee of autonomy. However, the end of the colonial era did not mean postcolonialism. Rather, having been ceded back to China, Hong Kong also handed over its incomplete independence and autonomy, and is becoming re-colonized. Real estate speculation by wealthy Mainland Chinese investors has given rise to soaring apartment prices, forcing ordinary people out of the city. Numerous projects in the name of “development” have gushed forth: public spaces where people used to spend time have been handed over to become new high-rise buildings, and a plan to raze a once-beautiful village to build an express railway linking China and Hong Kong is being carried out. Against this backdrop, students, young people, and artists in Hong Kong are creating their own history of protest in a struggle to realize a legitimate democracy. As recently as late September 2014, the Occupy Central movement has ignited in its demand for free direct elections of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive. Young people in Hong Kong continue to engage in a fight that appears to have no ending. It may well be that they know their actions will not bring about a dramatic change at the present. Yet it seems that they persist in solidarity because they believe that Hong Kong’s future—and the futures of following generations—will be bleaker if they do not take action now.

With Hong Kong’s current situation before us now, it is difficult not to be reminded of the 1980s democracy movement in Korea. Yet now, more than 30 years after the democracy movement, the reality in Korea is not promising. Instead, having experienced a recent series of tragic incidents and observing the government’s oblique reactions to them, we worry about whether Korea will revert back to the military dictatorship of the 1960s-1970s. No, perhaps “worry” is not correct—we starkly believe that this is becoming reality. A “blackout” Korean government controls the mass media, hiding the truth and constantly leaking suggestive news so as to deceive citizens and aggravate social divisions. Although we have sunken deeper and deeper into despair due to the seemingly endless human disasters and tragedies that occurred in 2014 (and have consequently neither addressed nor resolved any of these problems), we now cry out: Enough is enough. Perhaps it begins now. As Korea observes a present-day Hong Kong that evokes the image of Korea 30 years ago, Korea cannot help thinking that its circumstances are little better than Hong Kong now, or perhaps it is that, unlike Hong Kong, our present has become too difficult to express. And the sight of a bright yellow ribbon—unfurled in Korea to symbolize the safe return and commemoration of those missing in the Sewol Ferry Incident, but adorning the city of Hong Kong as a public symbol of the longing for democracy—compels one to draw a peculiar, yet melancholy, juxtaposition.

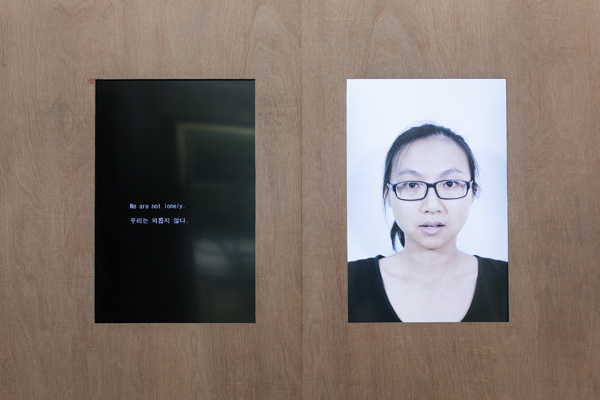

Addressing an era in which Korean society implicitly forces people to forget their pain, suppress their feelings, and restrain their expression, Korean artist Dongkyu Kim speaks of the need to take the time to share, understand, and express each another’s pain through language and gesture. In his work Verbal Concerto, Dongkyu Kim documented the process of a symbolic exchange between artists from different regions of the world. The Hong Kong and Korean artists wrote texts addressing the pressing issues and situations that they are facing today in their own countries, and then vocalized them by borrowing their Hong Kong (or Korean) counterpart’s voice. The Hong Kong artists read sentences in Korean aloud using a phonetic alphabet; likewise, the Korean artist read out sentences in Cantonese. Dongkyu Kim brought forward words that he had attempted to keep engraved deep in his heart—sentences full of “resolution” that he burned with desire to shout out—delivering a total of 30 sentences to the three Hong Kong artists.

In return, the Hong Kong artists each wrote and delivered their own sentences to Dongkyu. Clara expressed a longing for democracy and political reform, while Gum communicated the sense of despair that people in Hong Kong suffer due to lives that are starved for time between their livelihoods and meeting skyrocketing housing costs, as well as the sense of urgency that he feels to fight for a real democracy now, for the sake of the next generation. Sushan composed sentences in which she drew comparisons between her illness and the emptiness of Hong Kong life. It was no simple task for people who had just met for the first time to truly understand one another and work together, and the process of exchanging their respective languages progressed slowly, requiring seemingly endless repetition. Nonetheless, in the midst of hearing the words that they wanted to speak emerge—however unnaturally—from their counterpart’s voice, they identified the possibility of new meanings that can be invoked in the space between sentences, thus exploring a new means of solidarity.

The Hong Kong and Korean artists attempted to commune with each other in an “unknown” language. Speaking with an unknown language does not necessarily mean the impossibility of communicating with each other. Although it may have been difficult in itself to communicate in their respective “mother tongues” of Korean and Cantonese, in Dongkyu Kim’s words, what they shared was “behavioral language and verbal behavior.” They tried to utilize Chinese characters as an intermediary between Korean and Cantonese, to convey their thoughts in English (although it often fell short), and to understand each other using their imaginations. According to Kim, “I thought that the clumsy pronunciation that a native speaker hears would newly evoke the sentences’ meanings. What I did not expect is that the sentences that I read and the sentences the others read would cause semantic interference rather than a juxtaposition that draws parallel lines. Perhaps what we call solidarity is not the process of confirming commonality or learning the differences among individuals, but rather the process of arriving at a third meaning.”

In the space between their different languages, like the “communicative emptiness” that poet Eun-yeong Jin (citing Giorgio Agamben) describes, is a situation in which the possibility of communication can be transmitted and an indeterminate space appears, one that is not filled in with definite meaning such that disparate meanings may arise and circulate. The artists attempted to share and commune in this indeterminate space with “verbal behavior.” However, we know that in reality, politicians and the media establishment are undoubtedly trying to take control this empty space. When something that is different from the currently disseminated dominant meanings is communicated, they characterize it as a distorted symbol and fill in the empty space of communication by persuading people that the current means of communication is for the sake of the entire community.

The “empty communication” exposed in Verbal Concerto also appears in Dongkyu Kim’s prior works. The artist has maintained an interest in images that stay one step outside of the mainstream art scene and the media environment, utilizing objects such as street sculptures, abandoned statues of Buddha, and abstract paintings with unknown origin to question how these images signify and operate. Over the course of this process, he traverses multiple roles—a destroyer of icons, a pseudo-scholar, an art detective, and so on. Preceding the work Verbal Concerto, he undertook a performance in the area where the victims of the Sewol Ferry Incident’s bereaved families have been staging protests. He remarked that he had neither a specific intention nor purpose when he went there. However, starting with unconscious drawing, he filled pages and pages of white paper with black ink to the point of exhaustion so as to express the feelings of grief and rage that he could no longer avoid or bear. I do not know how he came to engage in this action, or what went through his mind during the performance. Perhaps he does not know, either. In this ritual-like performance, he used his body and abstract drawings to empathize with the bereaved families, expressing their inexpressible grief and agony together with his own pain.

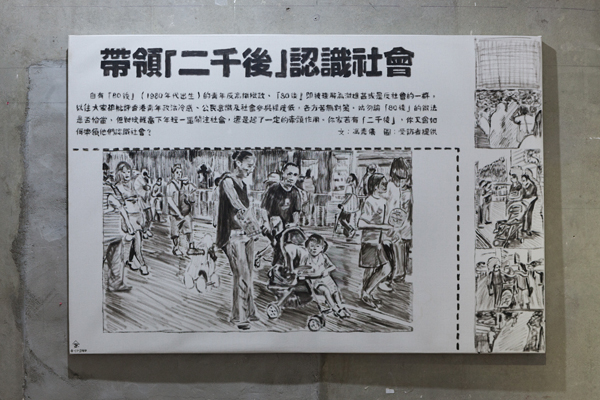

Using the vehicle of their diverse art practices, the Hong Kong artists participating in this exhibition warn that the Hong Kong government’s pro-China policies will ultimately shackle Hong Kong’s economy and cast an influence on the entirety of Hong Kong’s cultural and educational policy, thus paralyzing the consciousness of its citizens. These artists quietly encroach upon, or exploit, the media’s process of violent language communication that claims to stand for the clear and objective delivery of facts. In running the non-profit art space C&G Artpartment, artist duo C&G not only puts forth an effort to pursue the autonomy of Hong Kong’s local art scene, but also criticizes and searches for alternatives with regard to the cultural education polices in Hong Kong. C&G has received attention due to the duo’s unique performances that make their voices heard in the streets. In 2004, they dressed in traditional Chinese wedding outfits and held a wedding engagement at the annual July 1st protest rally in Hong Kong, and after having children, they pushed along strollers, taking part in various protests. Images of them actively engaging in social issues are subject to a good deal of media attention, and C&G utilizes these opportunities to deliver their voices to the mass media. However, C&G has stated that “information from the mass media crashes into us without boundaries, and yet it can also disappear all of a sudden, under the assault of the media. The power of the media cannot be neglected, since it definitely has the ability to turn ‘black’ into ‘white.’” From his own blurry and imprecise impressions, C&G’s Gum re-paints the media’s reports on himself in black and white oil paintings. In this process, he attempts not to create a portrayal that is closer to reality, but instead to recognize when to stop illustrating details in order to reveal to a precise image or message. Thus, he says, “these works not only allow me to re-examine my interviews with the media at that moment of time, but also to re-reconcile how the media portrays myself, and more importantly, to understand how I see the way the media sees myself.”

In May 2014, C&G organized a trivia quiz show incorporating significant but seldom acknowledged stories from the past 50 years of contemporary art and politics in Hong Kong that they unearthed during their residency at Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong. In Not as Trivial as You Think: Hong Kong Art Quiz, C&G invited four teams of artists, students, art critics, and art administrators, among others, and themselves took on the roles of show hosts, presenting a colorful and cheerful program. Utilizing a quiz based on true stories, C&G strategically exposed the problem that emerges where “the art ecology in Hong Kong is lopsided—seemingly dependent on a desire to consume and be consumed—whether it is to make a living out of the art market, or to consume art as entertainment and a lifestyle.” In the largest hall of the Art Basel Hong Kong venue, people in the Hong Kong art world and audiences spent a raucous yet meaningful time confirming the holes in Hong Kong art and pondering what is needed for a comprehensible art ecology.

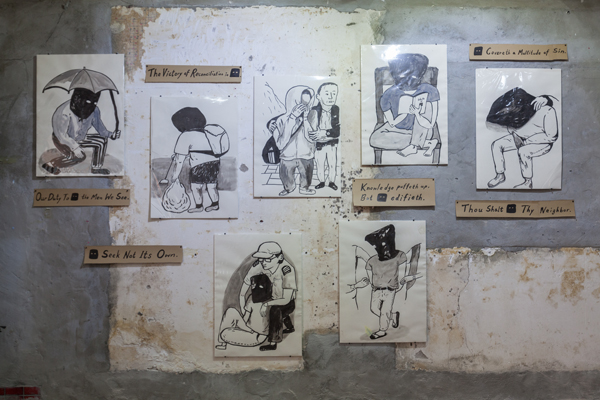

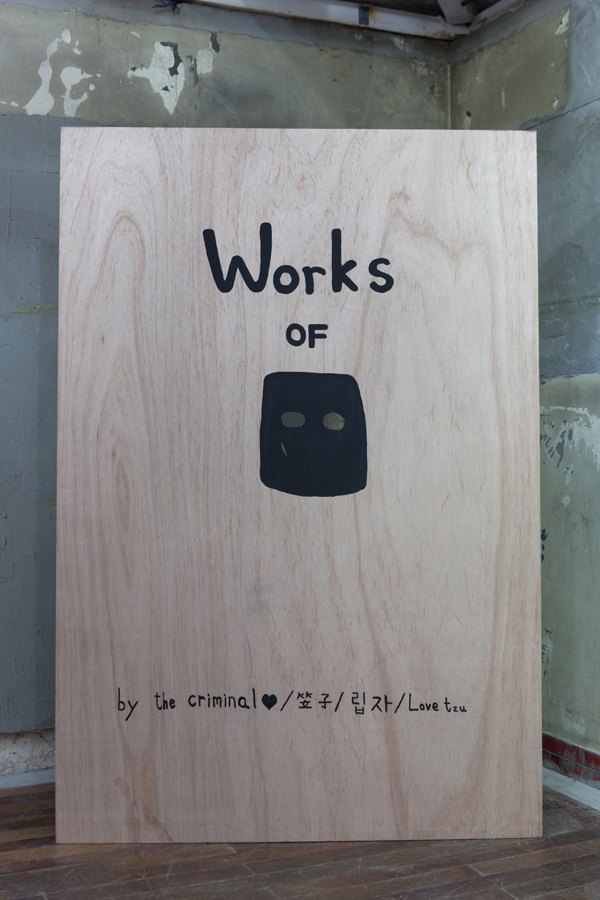

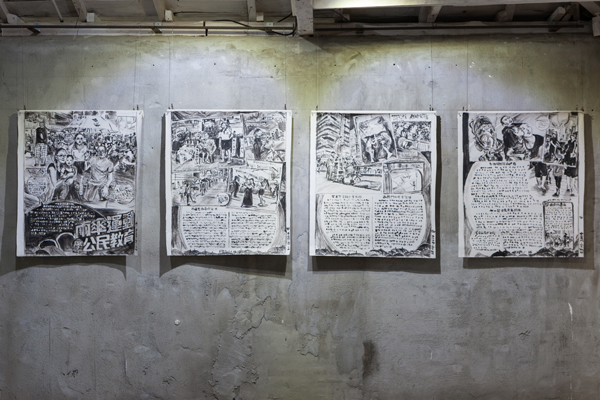

Sushan Chan works in print media formats such as newspapers, posters, books, and comics. She formerly worked with the community art space Woofer Ten as its art director, and published Woofer Post, a community newspaper focusing on issues involving the Yau Ma Tei neighborhood of Hong Kong where Woofer Ten is located. This newspaper, which was published in fifteen issues from January 2012 to July 2013, included not only the voices of members of Woofer Ten, but also many contributions from individual neighbors and shops. In Woofer Post, Sushan contributed a series of columns called Minor News, in which she collected small but significant pieces of news from local newspapers and illustrated them in comic form. However, the minor news that she selected is by no means trivial, as these stories in fact satirize the boundaries of crime, justice, ethics, and community. Likewise, she has also created a series of posters that addresses current issues by appropriating historical events and old stories. The poster World Common Sense 64 (2009) portrays cleaners who are busy scrubbing in the backdrop of Tiananmen Square, along with the words “The Cleanest Square on Earth: Tiananmen Square in China.” Tiananmen Square, where the June Fourth Massacre (also called “Bloody Sunday”) took place in 1989, has cleaned up the “blood” and has become a popular tourist attraction in Beijing. As Sushan notes, “Tiananmen Square cleaned away the blood and brainwashed its people, so it became the cleanest square on earth”; as such, it is her attempt to say that we should not forget this history. In her Criminal Series, she accentuates the fact that the black cloth bag that a suspected criminal wears over his or her head in Hong Kong can be a device that distorts the seriousness or lightness of a crime. In this manner, Sushan proposes that in reality, anyone can make a mistake or commit some type of crime, and questions whether one’s act is in fact a crime if one’s life has been threatened or one’s freedom of speech has been suppressed.

Through means of language, action, and art, the four artists in this exhibition assert that one must not become habituated to situations and conditions that are imposed from outside. Recognizing the danger of a “low burn,” and prior to the onset of a pain that cannot be undone, they proclaim that we should ignite the problems now and undergo a process of healing. But can an individual actually make a difference in a sea of empty promises, or will hollow words engulf him, like the waves that swallowed the Sewol? Can an umbrella—yellow or otherwise—protect against the approaching burn of censorship, or will it simply fan the flames? We have no choice but to wait for the answers to these questions.

Perhaps, now, what these artists’ works reflect more than anything else is the sensual power that only art can possess. When we sense the power of well-controlled brushstrokes as C&G repaints the images of the media’s portrayal of them into their own self-portraits, the equivocality that emerges when Sushan Chan depicts people wearing black hoods with black ink, and the sense of hands that radiates from Dongkyu Kim’s drawings, we are compelled to believe that the power of images is far superior to that of any words.

Sunghee Lee (Guest Curator)

Supported by

the Arts Development Fund of the Home Affairs Bureau,

the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

2014 Pool Production 《Low Burn: Low Voice connecting Hong Kong and Seoul》 PR image, design by EVERYDAY PRACTICE ⓒ EVERYDAY PRACTICE , Art Space Pool

2014 Pool Production 《Low Burn: Low Voice connecting Hong Kong and Seoul》 PR image, design by EVERYDAY PRACTICE ⓒ EVERYDAY PRACTICE , Art Space Pool

2014 Pool Production 《Low Burn: Low Voice connecting Hong Kong and Seoul》, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

2014 Pool Production 《Low Burn: Low Voice connecting Hong Kong and Seoul》, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Dongkyu Kim, 《Verbal Concerto》, 2014, two-channel HD video installation, dimensions variable, 6min 44sec , Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Dongkyu Kim, 《Verbal Concerto》, 2014, two-channel HD video installation, dimensions variable, 6min 44sec , Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Sushan Chan, 《The Criminal Series 》, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Sushan Chan, 《The Criminal Series 》, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Sushan Chan, 《The Criminal Series (Pages)》, 2014, ink on paper, 70x50cm (7 pieces), Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Sushan Chan, 《The Criminal Series (Pages)》, 2014, ink on paper, 70x50cm (7 pieces), Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Sushan Chan,《The Criminal Series (Covers)》, 2014, paint on wood board, 180x120cm (2 pieces), Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Sushan Chan,《The Criminal Series (Covers)》, 2014, paint on wood board, 180x120cm (2 pieces), Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Sushan Chan,《The Criminal Series (Drawings)》, pencil and ink on paper, 26x21cm each, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Sushan Chan,《The Criminal Series (Drawings)》, pencil and ink on paper, 26x21cm each, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Sushan Chan, Printed Material Archive, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Sushan Chan, Printed Material Archive, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

C&G, 《TVB Jade6:30 News 1 July 2007》, 2007, oil on canvas, 20.5x25cm(30 pieces), animation, 15seconds, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

C&G, 《TVB Jade6:30 News 1 July 2007》, 2007, oil on canvas, 20.5x25cm(30 pieces), animation, 15seconds, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool C&G, 《Not as Trivial as You Think: Hong Kong Art Quiz》, 17 May @014,Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre, highlights from documentary video Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

C&G, 《Not as Trivial as You Think: Hong Kong Art Quiz》, 17 May @014,Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre, highlights from documentary video Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Gum Cheng, 《Ming Pao Daily, 19 January 2010》, 2010, oil on canvas, 100x150cm, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Gum Cheng, 《Ming Pao Daily, 19 January 2010》, 2010, oil on canvas, 100x150cm, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Gum Cheng, 《Oriental Sunday, #878, 6 October 2014》, 2014, oil on canvas, 70x60cm, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Gum Cheng, 《Oriental Sunday, #878, 6 October 2014》, 2014, oil on canvas, 70x60cm, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Dongkyu Kim, 《From Forsythia to Ginkgo》, 2014, byproduct of performance, ink on paper, installation, dimensions variable, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool

Dongkyu Kim, 《From Forsythia to Ginkgo》, 2014, byproduct of performance, ink on paper, installation, dimensions variable, Photo by Bara Studio_kim joong won ⓒ Bara Studio, Art Space Pool