Aesthetics of an exquisite (manmade) view

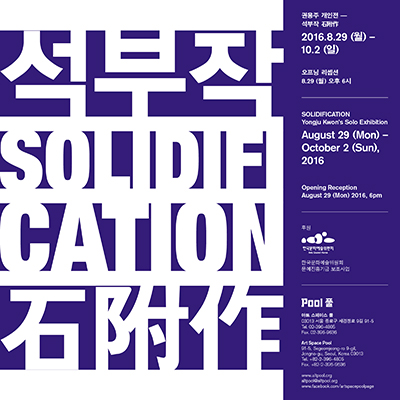

Seokbujak / Solidification /石附作

The “rocks” [seok, 石] in Yongju Kwon’s works are not inherently solid. They are, in fact, amalgamations of different objects that have been coated with cement. They were made solid through a process of “solidification.” It entails a process of “mount”-ing [bu, 附] plants onto the rocks and looking after them so that they take root and grow. In other words, this process of mixing artificial materials and manmade nature and the process of “create” (ing) [jak, 作] reflect the progression by which Yongju Kwon’s solo exhibition came to bear the title and theme of “Solidification.” The title further refers to the artist’s methodology and approach of translating a spontaneous, temporary, and ongoing state of flux into concrete works of art. Lastly, it recalls the artist’s discomfort and struggle with stasis and established patterns in his work as he continuously develops his art practice.

Recently, Yongju Kwon has attempted to reinterpret the activity of seokbujak [mounting on orchid rocks], a hobby in which one seeks to build communion with miniaturized pseudo-nature by transplanting plants such as moss, Aerides orchids, and wild flowers onto a natural-looking stone and caring for them. Kwon produces the works as follows: he applies cement onto prepared objects such as chunks of cement, egg cartons, waste paper, a mop, and the upper part of a broom, then he sprays water to create the shape of a rugged cliff, and finally he attaches Aerides orchids (which are accustomed to living in harsh environments like cliffs) onto the pseudo-cliff and carefully nurtures them so that they take root and grow. As manifested in this process of production, Kwon’s integration of work, hobby, and play carries with it a certain appeal. Naturally, Mounting on Rocks is made with a humorous touch. The mise-en-scene of cement mountains gently placed onto the heads of a mop and a broom, and the Aerides orchids together with them, is somehow silly, while a set of cement mountains protruding over entangled wires among the Aerides orchids is similarly ludicrous, and the rugged cliff made from recycled waste paper roughly tied with wrapping twine and with only one side covered with cement is absurd. However, at the same time, these unexpected scenes spur viewers to imagine what lies beyond the crests of the mountains. I assume this is what Kwon meant by “the function as a portal that makes an exquisite perspective (fantasy-paradise) out of a small-scale landscape, at least in one’s imagination.” Mounting on Rocks (2016) represents a breakthrough that enables Kwon to explore the familiar theme of the overlap between art and livelihood with a refreshingly different approach, and it also provides a clue as to how the artist exorcised the stagnant (or solidified) thoughts that occupied him at one time.

Yongju Kwon first began to present artworks in the art field in the late 2000s, and he has constructed his world of art over the past 10 years while managing his endeavors between his two identities as an artist and a worker. However, in most cases, he deliberately avoids dealing with the labor of art, or the artist’s labor. Rather, his works address the process of executing and reinforcing his different (yet indivisible) identities as a worker, maker, and exhibition technician. No matter how hard Kwon may try to resist this, the techniques he acquired in the course of the labor he performed to sustain his livelihood are already embedded in him and applied in his artwork. Such experiences have so deeply influenced his thoughts that it often seems that Kwon thinks and acts as a “worker.” This time, Yongju Kwon’s solo exhibition is designed to facilitate a loose dialogue among his works created as a result his vivid life experiences, and to trace the narratives generated by these works.

In order to make shapes, Kwon draws things out: things that hide well via a polished surface (i.e., a visual sleight of hand), and things that are normally hidden under a polished surface (e.g., miscellaneous rubbish and construction materials). Kwon’s sculptural installation works take shape by chance with things that are abandoned or will be abandoned, or with things that exist for the sake of a process—not its outcome—and that will eventually be concealed. His works embody the precarious lives of urban, working-class individuals and the imperfect reality that all of us belong to.

At one corner of the exhibition space is We Will Meet at the Top (2009), where a cement mountain with the shape of a crater has been placed in the center, and a picture of Baekdusan Mountain, a souvenir photograph, and a snapshot of a random place in a town hang from the wall. Kwon commented on how the puddle for the cement mixture at a construction site inspired him to make the crater of Baekdusan Mountain: “At that time, for an entire year, I had a job that needed me to work with cement. I had to make the puddle of cement every day, and that experience led me to adopt a similar shape and material for my work.” Yet the title of the work is ironic, as “We will meet at the top” is sheer magniloquence: the crater of the cement mountain that he produced is too damp to step on, and the top of Baekdusan Mountain—what the installation aims to emulate—is something that is both physically and ideologically difficult to reach. “Later we will meet at the top” is actually a trite and vapid expression favored by pretentious young men, especially when they are inebriated at parties. Similar to how the expression is empty, the title itself floats meaninglessly in the air when it encounters the reality of this work. And nearby, is Better a Live Coward than a Dead Hero (2009). Still primarily working with cement, Kwon utilized ready-made cement blocks instead of cement powder. Inscribed in block letters into the cement block is the Korean translation of the proverb, “Better a Live Coward than a Dead Hero,” which literally translates into Korean as: “Better to roll around in a field of shit while alive, in this world.” The space that exists between the English proverb and the Korean translation exposes a subtle but meaningful divergence in the rationales for living vs. mere survival. And it echoes a certain resignation about the futility of human ambition that one senses in the inaccessible peak of We Will Meet at the Top.

Among Kwon’s works is a type of work deriving from the various types of labor that the artist has himself performed. Some examples are Mounting on Rocks, We Will Meet at the Top, Better a Live Coward than a Dead Hero, and a series of works—which were not selected for this exhibition at Art Space Pool—comprising a pseudo-rock of Styrofoam, a gravestone, and a signboard onto which phrases are inscribed. Yet another type of Kwon’s works is one that contemplates the real world of labor, like Tying (2013/2016). In the next exhibition area, the viewer faces an installation of fluorescent dyed yarn in a space that has the atmosphere of a shabby small-scale domestic production site. Traversing through different spaces and times is a cross-edited video interview with the artist’s mother, who speaks in a reminiscent yet dry tone about her youth spent working at a textile factory, and with a textile factory worker in Thailand. While a sense of lyricism in the air at the Art Space Pool exhibition space leads viewers to associate the space with the textile factory from the memories of the artist’s mother, the video depicts the repetitive movements of a machine in an almost workerless factory. A silk cloth produced by the automatic machine in the video hangs from the ceiling to the floor in the exhibition hall, and the will to survive referenced in the phrase weaved into the silk cloth—“Dragged and left alone in a gravel field, you will live on, even in a vast field of sand, you will lay the cornerstone to build a house…”—is more driven and poignant than the implied hesitation of the proverb, “Better a live coward than a dead hero.” Installed in a small room in a corner of the exhibition space, Underground Sewing Factory amplifies the lyricism and nostalgia that one senses in the yarn installation in Tying and pushes it further to the point of fantasy. It could be that what Kwon seeks to deliver is a sense of hopefulness. Just like the mundane objects used in Underground Sewing Factory (including *a bowl of water, pieces of glass, and a mirror) create rainbows when struck by rays of light passing through the window, a ray of light will shine on a life fraught with adversity.

Entering the underground space in the building next door, the viewer encounters Waterfall (2016), a scene that appears to intermix a construction site and a manmade waterfall in the city.Yongju Kwon has produced six or seven different versions of Waterfall since Waterfall_Structure of Survival, which he exhibited at his 2011 solo show at Seoul Art Space Mullae. Waterfall, installed in Art Space Pool’s underground courtyard, has been realized in a form that reduces the work to its basic elements, making it most similar to the rough drawings of imaginary recreational facilities in the city that the artist made when he first conceived the Waterfall series. The previous works in the Waterfall series revolved around two opposing forces: one, the structure itself that maximizes the materiality of the work as a whole by using miscellaneous objects like recyclable materials and waste materials; the other, the force of the falling water that negates this maximized materiality. However, the Waterfall installed in Art Space Pool distinguishes itself from the previous works in the series by the way it is produced. Wooden panels are measured and cut according to the rough sketch so as to represent the two-dimensionality of the drawing, and subsequently the panels are set upright in layers of two or three to make a wall. The panels are covered with blue tarpaulin and tied together with industrial rubber cord. The scene actually resembles one that you might see in the corner of a construction site, where construction materials are either kept separately in order to protect them from the elements or are covered and bound tightly when loaded on a truck. If the previous versions revealed the objects that could lay under the blue tarpaulin, this one covers these objects to achieve the aesthetics of an exquisite (manmade) view evoking the shape of a mountain and rugged cliffs similar to those in Mounting on Rocks. Perhaps because its familiarity recalls the scene of the construction site, Kwon’s manmade Waterfall somehow feels more natural and realistic than the artificial waterfalls in urban settings that imitate the exquisite views found in (real) nature. A video projected from the small screen on the table installed in front of the waterfall depicts scenes of falling water made in earlier works in the Waterfall series.

Through the miniature landscapes of Mounting on Rocks, Kwon seeks to convey the concept of a “portal”—an exquisite perspective, or what he calls a “fantasy-paradise” in the world of one’s imagination. The viewer encounters another jarring “portal” in Waterfall due to the supposedly realistic yet actually manmade landscape created by the familiar unfamiliarity of the manmade blue waterfall and the video of artificial scenery displayed on the small video screen. The contrasts and contradictions of these “portals”—reality vs. paradise, manmade vs. imagination,natural vs. artificial, rawness vs. refinement, solidification vs. fluidity—reach an unexpected yet striking visual climax when one sits in Pool’s underground courtyard and catches a fleeting glimpse of the rich late afternoon sunlight hitting the glossy blue tarpaulin. In the space of a moment, it is an exquisite window to another world. Given the opportunity, I would suggest that you take a rest downstairs for a quiet moment and see for yourself.

Sunghee Lee, Director, Art Space Pool

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》

Yongju Kwon, Mounting on Rocks, 2016, orchid, cement, mop, broom, etc., dimensions variable

Yongju Kwon, Mounting on Rocks, 2016, orchid, cement, mop, broom, etc., dimensions variable

Yongju Kwon, Mounting on Rocks, 2016, orchid, cement, waste paper, egg crate, etc., 61x29x31cm

Yongju Kwon, Mounting on Rocks, 2016, orchid, cement, waste paper, egg crate, etc., 61x29x31cm

Yongju Kwon, Mounting on Rocks, 2016, orchid, cement, wire, string, etc., 185x29x19cm

Yongju Kwon, Mounting on Rocks, 2016, orchid, cement, wire, string, etc., 185x29x19cm

, 2014_01.jpg) Yongju Kwon, Multi-Use Wall, 2014, single channel video, color, sound, 6mins

Yongju Kwon, Multi-Use Wall, 2014, single channel video, color, sound, 6mins

, 2013,2016_스틸컷05.jpg) Yongju Kwon, Tying, 2013/2016, single channel video (color, sound, 27mins), colored threads, brass, jacquard printed silk, fluorescent lamps, dimensions variable

Yongju Kwon, Tying, 2013/2016, single channel video (color, sound, 27mins), colored threads, brass, jacquard printed silk, fluorescent lamps, dimensions variable

We Will Meet at the Top, 2009, cement, found picture frames, color prints, dimensions variable

We Will Meet at the Top, 2009, cement, found picture frames, color prints, dimensions variable

Better a Live Coward than a Dead Hero, 2009, engraving on cement blocks, 45x20x 150cm

Better a Live Coward than a Dead Hero, 2009, engraving on cement blocks, 45x20x 150cm

Waterfall, 2011/2016, tarpaulin, water pumps, wood, found potted plant, table, rubber straps, 420x450x260cm

Waterfall, 2011/2016, tarpaulin, water pumps, wood, found potted plant, table, rubber straps, 420x450x260cm

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》, Photo by Bara Studio_Kim Joong Won ⓒ Yongju Kwon, Art Space Pool

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》, Photo by Bara Studio_Kim Joong Won ⓒ Yongju Kwon, Art Space Pool

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》, Photo by Bara Studio_Kim Joong Won ⓒ Yongju Kwon, Art Space Pool

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》, Photo by Bara Studio_Kim Joong Won ⓒ Yongju Kwon, Art Space Pool

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》, Photo by Bara Studio_Kim Joong Won ⓒ Yongju Kwon, Art Space Pool

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》, Photo by Bara Studio_Kim Joong Won ⓒ Yongju Kwon, Art Space Pool

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》, Photo by Bara Studio_Kim Joong Won ⓒ Yongju Kwon, Art Space Pool

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》, Photo by Bara Studio_Kim Joong Won ⓒ Yongju Kwon, Art Space Pool

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》, Photo by Bara Studio_Kim Joong Won ⓒ Yongju Kwon, Art Space Pool

2016 Pool Production 《Yongju Kwon: Solidification》, Photo by Bara Studio_Kim Joong Won ⓒ Yongju Kwon, Art Space Pool